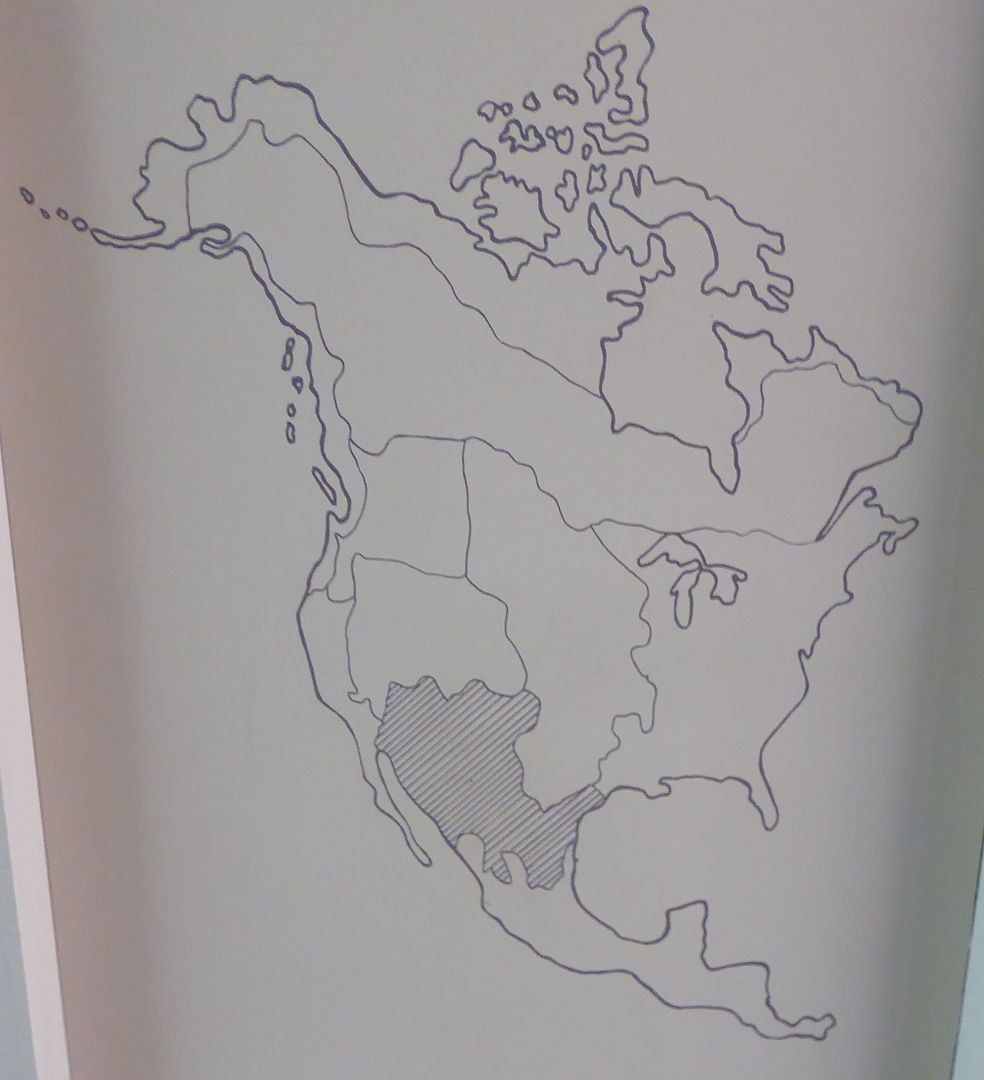

The Southwest Culture Area is a culturally diverse area. Geographically it covers all of Arizona and New Mexico and includes parts of Colorado, Nevada, Utah, and Texas as well as parts of the Mexican states of Sonora, Baja California Norte, and Chihuahua. Much of this area is semi-arid; part of it is true desert (southern Arizona); and part of it has upland and mountain ranges which support conifers.

The Yuman-Speaking Cultures

The Yuman cultural tradition is in the desert and semi-desert area along the Colorado and Gila Rivers. This area includes parts of Arizona, California, and the Mexican states of Sonora, and Baja California Norte.

Among the Walapai, the dead were traditionally cremated along with their possessions. The souls of the dead departed for the ancestral land of Tudjupa in the west. There was also an annual burning of clothing and food to commemorate the dead. The practice of cremation, however, was stopped by the U.S. Army in the nineteenth century as the United States required Christian burials.

Traditionally, the Havasupai observed very little ceremony regarding the disposal of the dead. The dead were either cremated or placed in caves or rock cairns.

Among the Mohave, the deceased was cremated upon a funeral pyre. Orators would make speeches about the virtues of the deceased and songs would be sung. Articles burned with the deceased would accompany the soul to the land of the dead. After death there was a taboo on mentioning the name of a dead person.

Among the Cocopa, the soul leaves the body at the time of cremation and goes to the spirit land near the mouth of the Colorado River. However, twins go to a different place and are continuously reincarnated. After death the name of the deceased is never mentioned.

Among the Quechan, it is felt that the signs of death begin to appear about three months in advance. These signs include dreams, unexplained noises, and the owl. With regard to the owl, Bernadine Swift Arrow, in an article in The Indian Historian writes:

“The owl is believed to be a reincarnated member of the tribe, and in some respects is doing a service, though not one of joy.”

After death, the Quechan place the body in the Cry House where the casket is placed so that the head faces east. For four days friends come by to say farewell. During the four days of morning, the family fasts. The soul of the deceased is free, but will remain earth-bound until the funeral pyre is lit. At the funeral pyre, the casket is opened, the body is then placed on the pyre, on the side with the face toward the north. Logs are placed on top of the body and blankets are strewn on top. According to Bernadine Swift Arrow:

“The people stand back, watching for signs of the deceased’s departure; always, there is a sign.”

The Piman-Speaking Cultures

The Sonoran Desert of Arizona and the Mexican state of Sonora are home to a number of Piman-speaking groups, primarily the Tohono O’odham (Papago) and Akimel O’odham (Pima). The Sonoran Desert is an area of very hot summers (high temperatures may reach 120° F) and relatively little rain. The Piman-speaking peoples are the cultural descendants of the Hohokam, an agricultural people who flourished between 600 and 1450.

The Pimawere the village agriculturists of central and southern Arizona. The Pima call themselves O’odham which means “we, the people”. They are divided into four basic groups: (1) River Pima in Central Arizona (Akimel O’odham); (2) Tohono O'odham (also known as Papago) in southern Arizona and northern Sonora; (3) Pima Bajo in Mexico; and (4) the Sobaipuri. The Sobaipuri were driven out by the Apache and Spanish and intermingled with the other Pima groups. Traditionally they occupied the San Pedro River valley from Fairbank, Arizona, north to the Gila River junction, and the Santa Cruz River valley north to Picacho.

The dead were buried in a rock crevice and covered with stones or in a stone cairn roofed with logs. To accompany the spirit on its four-day journey to the Underworld in the east, food and possessions were also interred with the body. A short speech by a relative usually accompanied burial. In this speech, the deceased would be asked not to return.

Regarding the Tohono O’odham, Tom Bahti, in his book Southwestern Indian Ceremonials, writes:

“Disposal of the corpse took place soon after death as the ghosts of the deceased were greatly feared. Formerly burial was made in a rock crevice and covered with stones or in a stone cairn roofed with logs. Food and possessions were placed with the body in the grave to accompany the spirit on its four day journey to the Underworld ‘somewhere’ in the east.”

Among the Tohono O’odham, warriors killed in battle were cremated by scalp takers.

Among the Akimel O’odham the custom was to destroy a house where death had occurred and to build a new house a few meters away.

The Hohokam cremated their dead. Along with the body, pottery, palettes for preparing body and face paints, and ornaments were also burned.

The Navajo and Apache

The Athabascan-speaking people – the Navajo and the Apache – migrated into the Southwest from the area north of Edmonton, Alberta. In the late 1300’s and early 1400’s groups of hunting and gathering Athabascans began arriving in the Southwest from the far north in Canada. These were the ancestors of the Navajo and Apache peoples. While there are some scholars who feel that the Navajo and Apache could have begun arriving in the Southwest as early as 800 CE and some who feel that it was as late at 1500 CE, most tend to place their arrival between 1200 and 1400.

When the Spanish entered New Mexico, they recorded that the Tewa referred to one of the neighboring tribes as Navahú, in reference to large areas of cultivated lands. This is in reference to the Navajo practice of dry-farming in arroyos, and cañadas (canyons). The Tewa also referred to these newcomers as Apachü which means strangers and enemies. The Spanish would later refer to these people as Apache de Navajó meaning the Apaches with the great planted fields.

Among the southwestern Athabascan groups there is a fear of death and of dealing with both the bodies and the possessions of dead people. Among the Jicarilla Apache, for example, there is a great effort to keep children from seeing a dead person. In addition, children do not associate with other children who have family members who have recently died until the family has been cleansed by the proper ceremonies. There is a concern that children may be marked by the aura of death.

With regard to the Chiricahua Apache, at death the spirits begin a four-day journey to the spirit world. For the Chiricahua, open burial sites are very dangerous between the moment of death and the time when the grave is covered. During this time the spirit of the deceased is loose and free. It is thus able to cause mischief or harm. Funeral rites are expected to expedite the spirit’s journey.

Traditionally among the Navajo, the body of a dead person was left on the ground in the hogan (home) which was then abandoned, or the body was immediately buried. The body was allowed to decompose because their memory, thoughts, and descendants are the part which lives on. The idea of putting someone in a coffin or putting chemicals in the body to preserve the corpse is viewed with disgust by traditional Navajo.

At death, the personal property of a Navajo is buried with the corpse or it is destroyed. Traditionally, the name of the deceased is not mentioned for one year following death. After this year, the name of the deceased is rarely mentioned.

When a Navajo who has lived a full and long life dies, there is no period of mourning as it is felt that the spirit is ready to travel to another world. There is no dread of touching or handling the corpse of an old person. In his book Language and Art in the Navajo Universe, anthropologist Gary Witherspoon writes:

“For the Navajo death of old age is considered to be both natural and highly desirable.”

With regard to life after death, this is an issue of little concern for most Navajo. They feel that they will find out when they die and, in the meantime, this is something they have no way of knowing anything about and therefore they should not waste time thinking about it. The Navajo cultural orientation is towards life, toward making this life happier, more harmonious, and more beautiful.

In his 1958 book A Profile of Primitive Culture, Elman Service writes:

“The Navaho do not believe in a ‘happy hunting ground’ type of life after death.”

The afterworld is viewed as being to the north and underground. The recently deceased are guided by their dead kin on a journey that takes four days.

For the Navajo, birth and death are seen as opposites: one cannot exist without the other. Gary Witherspoon reports:

“Life is considered to be a cycle which reaches its natural conclusion in death of old age, and is renewed in each birth. Death before old age is considered to be unnatural and tragic, preventing the natural completion of the life cycle.”

The Pueblos

In northern Arizona and New Mexico there are several Indian nations who traditionally lived in compact villages. The Spanish used the word pueblo which means “town” in referring to these people. While the Pueblos are usually lumped together in both the anthropological and historical writings as though they are a single cultural group, they are linguistically and culturally divergent. The Pueblo people speak six mutually unintelligible languages and traditionally occupied more than 30 villages. The Pueblos share some features – farming, housing – but they are very different in others.

Writing about Pueblo funerals in general and the practice of placing food with the body, religion professor Henry Bowden, in his book American Indians and Christian Missions: Studies in Cultural Conflict,reports:

“If persons were thought to have led a good life, their survivors provided only a small amount of food, because they would need but little sustenance in traveling straight to the afterworld. If the departed souls had not been particularly virtuous, they received more food for the difficult journey that lay ahead.”

Among the Keresian-speaking Pueblos of the Rio Grande area, death is viewed as a natural and necessary event: if there were no death, then soon there would be no room left in the world. After death, both the soul and the guardian spirit leave the body but remain in the home of the deceased for four days. Then they journey to Shipap, the entrance to the underworld. The virtue of the deceased then determines the assignment to one of the four underworlds. Those who enter the innermost world become Shiwana (rainmakers) and return to the villages in the form of clouds.

Among the Zuni, Tom Bahti, in his book Southwestern Indian Ceremonials, reports:

“At death the corpse is bathed in yucca suds and rubbed with corn meal before burial.”

The spirit of the dead lingers in the village for four days. During this time the door to the deceased’s home is left open to permit the entry of the spirit. On the morning of the fifth day the spirit goes to Kothluwalawa beneath the water of the Listening Spring. Here the spirit becomes a member of the Uwannami (rainmakers). Members of the Bow Priesthood become lightning makers who bring water from the six great waters of the world. The water is poured through the clouds in the form of rain. The clouds are the masks worn by the Uwannami.

Archaeologist Kurt Dongoske, in his chapter in Repatriation Reader: Who Owns American Indian Remains?, explains the Hopi concept of death:

“Hopis believe that death initiates two distinct but inseparable journeys, that is, the physical journey of the body as it returns to a oneness with the earth and the spiritual journey of the soul to a place where it finally resides.”

Among the Hopi, Tom Bahti reports:

“At death the hair of the deceased is washed in yucca suds and prayer feathers are placed in the hands, feet, and hair.”

A mask of cotton is placed over the face of the dead to represent the cloud mask which the spirit will wear when it returns with the cloud people to bring rain to the village.” According to Tom Bahti:

“Women are wrapped in their wedding robes; men are buried in a special blanket of diamond twill weave with a plaid design.”

Four days after burial the spirit leaves the body and begins a journey to the Land of the Dead. They enter the underworld through the sipapu (sacred hole) in the Grand Canyon where they meet the One Horned God who can read a person’s thoughts by looking into the heart. Those who are virtuous follow the Sun Trail to the village of the Cloud People.

With regard to Hopi burials, anthropologist Mischa Titiev, in his book The Hopi Indians of Old Oraibi: Change and Continuity, reports that:

“Clothing, water, and piki are placed with a corpse for the soul’s use. The grave is sealed with rocks.”

In many cases the Hopi will use a quilt as a burial shroud.

When a kikmongwi (chief) dies, the staff which has symbolized his authority during his life is buried with him. In addition, his body is painted with symbols for important ritual occasions.

Among the Hopi, the spirits of children who die before they are initiated into a kiva return to their mother’s house to be reborn.

With regard to the importance of ancestors—Hisatsinom—to Hopi culture, archaeologist Kurt Dongoske writes:

“These ancestors are of great significance in the Hopi religion, and the Hopi people feel strongly that their physical remains need to be treated with respect. The Hopi people believe that their ancestor who were laid to rest at these archaeological sites were intended to—and continue to—maintain a spiritual guardianship over those places.”

The Hopi see the clouds which bring water to their villages as ancestors and thus they petition their departed ancestors to return and to bring with them the life-giving rain. In this way, the Hopi view death as a return to the spiritual realm and from this comes more life in the form of rain.

Among most of the Pueblos, life after death is the same as before death: the deceased journey to a town where they join a group with which they were associated in life. Only the Hopi express the idea of punishment after death.

At Cochití, when a person dies, an ear of blue corn with barbs at the point is placed in the corner of the room where the death occurred. This ear of corn represents the soul of the deceased which will linger in the area for a while.

In commenting about Pueblo resistance to Christianity, anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons, in her 1939 book Pueblo Indian Religion, writes:

“The Pueblo idea of life after death as merely a continuation of this life is incompatible with dogmas of hell and heaven. In this life the Spirits do not reward or punish; why should they after death?”

Religion professor Henry Bowden reports that “the Pueblo cosmology did not recognize a place of eternal punishment.”

Indians 101

Twice each week Indians 101 presents a variety of American Indian topics, including histories, biographies, museum tours, and cultural profiles. More from this series about Southwestern Indians:

Indians 101: The Southwestern Culture Area

Indians 101: Pueblo Indian Pottery

Indians 101: Hopi Political Organization

Indians 101: The Athabascan-Speaking Groups in the Southwest

Indians 101: A Tohono O'odham Village

Indians 101: A Very Short Overview of the Mohave Indians

Indians 101: Southwestern Baskets in the Maryhill Museum (Photo Diary)