The Inuit, also known as Eskimo, are native peoples of the Arctic Culture Area, a region which includes the Aleutian Islands, most of the Alaska Coast, the Canadian Artic, and parts of Greenland. It is an area which can be described as a “cold” desert. The area has long, cold winters and short summers. During the summer, the tundra becomes boggy and difficult to cross. While this is a harsh environment for humans, the Inuit have lived here for thousands of years.

In general, one of the basic features of the various Inuit groups is animism, a religious view in which all things, both animate and inanimate have souls. Writing about the Saint Lawrence Island Eskimo in the Handbook of North American Indians, Charles Hughes describes animism:

“Most features of observable nature were thought to have indwelling spiritual essences, in some cases capable of taking diverse forms. Rocks, mountains, and other features of landscape were included under such a spiritual umbrella.”

The Inuit were traditionally a hunting and gathering people. They hunted a variety of sea and land mammals, engaged in fishing, and gathering wild plant foods and fibers. The Arctic is an inhospitable world and food insecurity often characterizes life in this region. As a consequence, Inuit religion often sought to reduce this insecurity. In his book Native American Religions: A Geographical Survey, John J. Collins writes:

“If one were to assess the basic tenor of Eskimo behavior with a brief characterization one might say that, positively, they attempted to control the security of their food supply by engaging in hunting rituals and magic and that, negatively, they attempted to avoid the supernatural danger they believed so clearly to be manifested in their hostile physical environment.”

Survival in the Arctic and success in hunting required spiritual help. Writing about the Nunivak Eskimo in the Handbook of North American Indians, Margaret Lantis reports:

“Spirit powers, objects containing those powers, and songs derived from and invoking the powers form the core of the religion. Nothing important could be accomplished without the help of an ínẏu.”

Animals

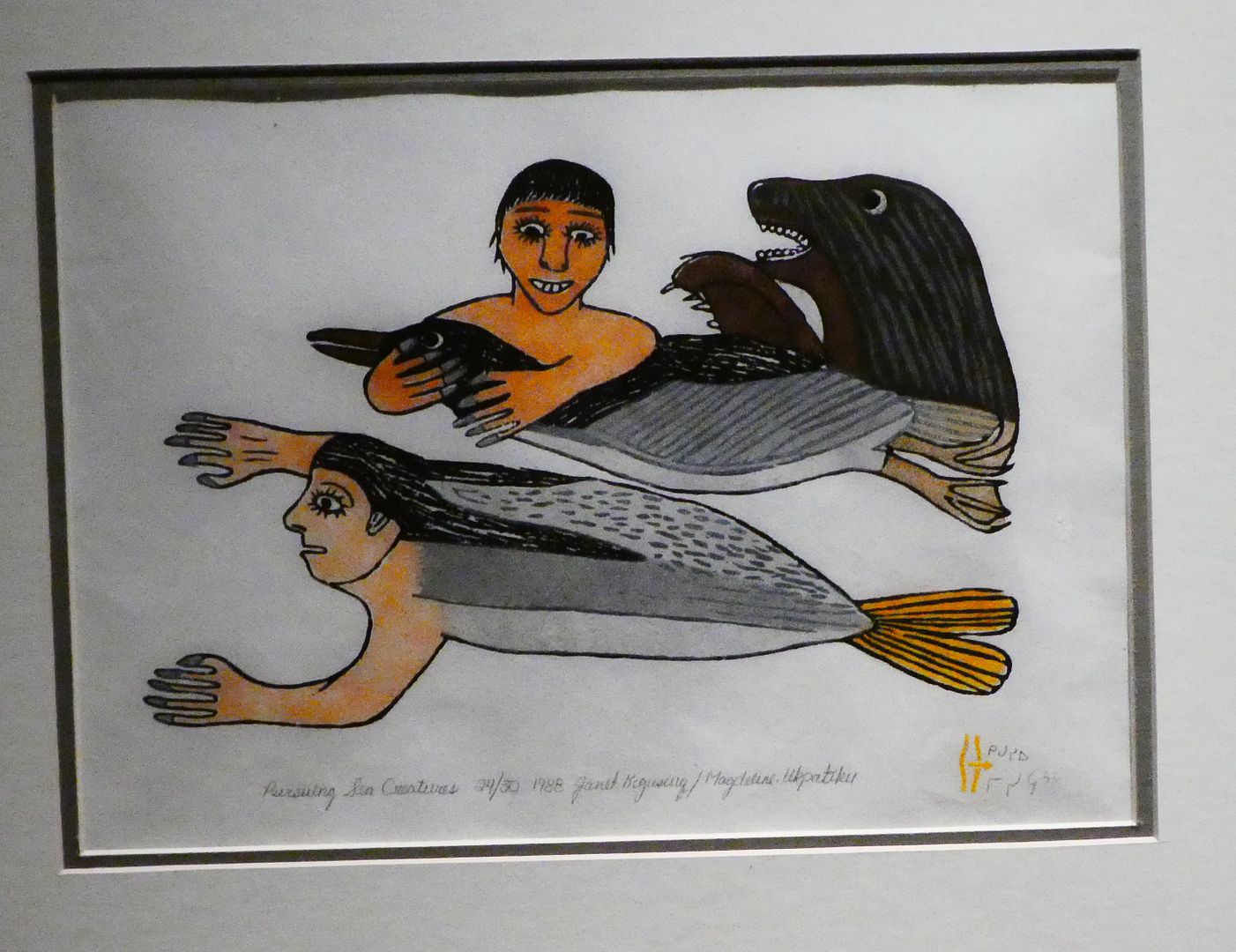

An important part of the Inuit worldview is the connection between humans and animals. In his entry on the Inuit in the Encyclopedia of North American Indians, Charles Smythe writes:

“Animals were thought to resemble humans in having souls or spirits that could think, feel, and talk. Eskimos believed that animals would give themselves voluntarily to the hunter who acted properly toward them, and the purpose of many ritual practices was in fact to show respect for and give thanks to the spirits of animals taken for food.”

Animals—mammals, birds, fish—could also take human form, looking and speaking like human beings. It is important for hunters to be able to maintain a perfect equilibrium with the animals and that, in turn, means keeping a peaceful relationship with the powers that regulates them. In his book A Profile of Primitive Culture, Elman Service writes:

“Animals have souls or spirits just as humans do; therefore, a slain animal has left a ghost which must be treated ritualistically like a human soul, so it will not become vengeful.”

While all things have souls, the souls of animals, especially animals which are hunted and provide food and clothing for the people, were most important in daily life. Writing about the Saint Lawrence Island Eskimo, Charles Hughes reports:

“But more important in the affairs of men were the souls of animals—seals, walruses, whales, polar bears—that were the quarry in the life-and-death encounters out on the sea. The souls of these animals were conceived to be very much like those of human beings.”

In the Arctic, as in many other regions of the world, the souls of animals could be reincarnated and harvested by the hunters.

The spiritual nature of animals was an important element of Inuit religion. Writing about the North Alaska Coast Eskimo in the Handbook of North American Indians, Robert Spencer reports:

“An elaboration of folklore and myth demonstrates that animals were morally and intellectually superior to men, that the game hunted allowed itself to be taken or could be coerced by ritual and magic.”

The spiritual and physical connection between humans and animals was an important part of the Inuit worldview. In her article on shapeshifters in Indian Country Today, Rachel Attituq Qitsaulik writes:

“In Inuit culture, all human beings have ‘personal animals,’ those that are friend or foe (i.e., an animal that one must especially respect, or altogether avoid).”

Taboos

Things which humans must avoid doing—commonly known as taboos—helped to ensure that the animals would allow themselves to be harvested by Inuit hunters. Common taboos were restrictions on eating certain foods and/or certain parts of the animal. In his chapter on the Polar Eskimo in the Handbook of North American Indians, Rolf Gilberg writes:

“They believed in the presence of certain mystical powers in nature that were easily offended and could become dangerous and malevolent.”

Writer Sheila Nickerson, in her book Midnight to the North: The Untold Story of the Inuit Woman Who Saved the Polaris Expedition, reports:

“…animal and human life are inextricably bound and kept in balance with one another by mutual respect and carefully observed taboos.”

Writing about the Inuit of Quebec in the Handbook of North American Indians, Bernard Saladin d’Anglure reports:

“To maintain the cosmic order and assure the reproduction of life the Inuit imposed a complex system of prescriptions and prohibitions, especially in two broad domains particularly related to this reproduction: in hunting and relations with game animals, and in procreation and relations with children.”

To avoid offending the spirits of the animals, the Inuit had to observe a number of taboos. It was not just the hunters whose lives were regulated by taboos, but also others in the family. Steve Langdon, in his book The Native People of Alaska, mentions taboos observed by wives to assist in their husband’s hunting:

“These included a broad range of activities such as cutting skins at certain times, eating certain foods or looking in certain directions.”

When taboos were broken it would bring bad luck to the husband’s hunting efforts.

The Soul

Writing about the Iglulik in the Handbook of North American Indians, Guy Mary-Rousselière reports:

“The notion of the soul was fundamental. All that exists has a soul or can have one.”

Each human has two souls: the breath of life and the soul proper. In addition, a person’s name, if inherited from an ancestor, may also have a soul.

With regard to the Polar Eskimo concept of the soul,Rolf Gilberg writes

“Each person had an immortal soul, a body spirit, and a name spirit. The soul was outside the body, following it around like a shadow; when the soul left the body, the person became ill.”

After death, the soul meets the ancestors in the sky or in the sea.

Among the Iglulik and other Inuit groups animals have souls and when they are killed the soul takes over a new body. Thus, it is important not to offend the animal’s soul so that it will offer itself again to the hunter.

Mythological Beings

There were also a number of mythological beings. Writing about the Nunivak Eskimo in the Handbook of North American Indians, Margaret Lantis reports:

“The nonhuman, nonanimal species were dwarfs, of two or more kinds and very common; giants, more rare; half-people, being only one side of a person, and half-birds; creatures that were half-human and half-animal or on whom one side of the face was normal, the other side distorted; wanderers, who were formerly human; a spirit with a large mouth on the chest; a string-figure spirit; the northern lights, which were walrus spirits playing ball with a human skull; water monsters in the lakes; a large man-worm with a human face on the head; a caribou with antlers branching like a willow; Big Eagle; and Raven.”

The moon was also an important entity and Margaret Lantis writes:

“A male moon spirit would come to the earth to get a wife or to help a mistreated person, and the shaman might journey to the moon to get help.”

Among the Netsilik there were three major deities. In his chapter on the Netsilik in the Handbook of North American Indians, Asen Balikci reports:

“Nuliayuk, a goddess living in the depths of the sea, was considered the mother of both sea and land animals; Nârssuk or Sila, the giant baby, was the weather god, master of the wind, rain, and snow; Tatqiq, the moon spirit, was a deity generally well disposed toward mankind.”

Indians 101

Twice each week—on Tuesdays and on Thursdays—this series explores various Native American topics. More about traditional religions from this series:

Indians 101: Outlawing the potlatch in Canada

Indians 201: Peyote and the Native American Church

Indians 101: A brief introduction to tribal religious traditions

Indians 101: Kwakiutl supernatural beings

Indians 201: A very short overview of Kiowa religion

Indians 101: Ceremonies of the Great Basin Indian Nations

Indians 101: A brief overview of Pawnee spirituality

Indians 101: A very short overview of Northern Plains Indian spirituality